Ballad Singing

In general parlance, the word “ballad” can refer to all sorts of songs—from romantic pop songs to folk-revival protest anthems. In the North Carolina mountains, ballads are traditional songs, usually sung unaccompanied, and often with origins that stretch back centuries to the British Isles. Parallel strains of Cherokee and African American traditional song enriched the Anglo/Celtic music brought by early white settlers, and new songs entered the tradition as singers chronicled the current events of their day within the ages-old ballad form.

Ballads are sometimes known simply as love songs in the Blue Ridge, even though the ones that are about love more often tell of love gone catastrophically awry than ending happily; in fact, Appalachian ballads are notoriously violent, sometimes even gory, their tales of war, treachery, and the occasional man-eating monster being the stuff of nightmares. Occasionally, though, they end with virtue rewarded, cleverness triumphant, and true lovers joined. Whether happy or dark, mountain ballads are gripping and beautiful.

Songcatching in the North Carolina mountains

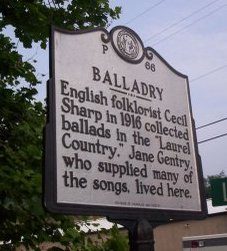

There is perhaps nowhere in America with a deeper or more widely recognized ballad tradition than the North Carolina mountains. The region has been a draw for ballad scholars (sometimes referred to as “songcatchers”) and field recorders for more than a hundred years, including the likes of Cecil Sharp and Alan Lomax. Many of North Carolina’s most renowned ballad singers have come from Madison County—particularly around the area known as Sodom Laurel—and from the Beech Mountain section of Avery and Watauga Counties.

Other folksong collectors working in the region included Olive Dame Campbell, who trailblazed for Cecil Sharp and novelist and folklorist Dorothy Scarborough, who authored the collection A Song Catcher in the Southern Mountains. The work of these two female folksong collectors inspired the 2002 feature film Songcatcher, filmed on location in the North Carolina mountains.

Ballad singers

The National Endowment for the Arts awarded a 2013 National Heritage Fellowship to Madison County’s Sheila Kay Adams, perhaps the most influential traditional ballad singer alive today. Adams comes from a long line of singers, members of the renowned Norton, Chandler, and Wallin musical families. Other North Carolina ballad singers who received the National Heritage Fellowship include:

- Cullowhee’s Mary Jane Queen (2007)

- Madison County’s Doug Wallin (1990)

- Guitarist Doc Watson (1988)

- Storyteller Ray Hicks (1983)

Other legendary bearers of the tradition include:

Among those carrying the tradition today are:

Events featuring ballad singing

There are many opportunities to hear today’s great mountain ballad singers—in concerts, on recordings, and at festivals such as the Bluff Mountain Festival (held in June in Hot Springs) and the Bascom Lamar Lunsford Festival (in October at Mars Hill University).

Visit the Down The Road on the Blue Ridge Music Trails Podcast Library to hear more about how the Settlers Brought Ancient Ballads to the Mountains and explore many bluegrass and old-time music stories, performers, and traditions across the mountain and foothills counties of Western North Carolina.